Strike Commander Remake, the story so far

I’m going to share how I started working on the Strike Commander remake. From its beginnings and discovering the libRealSpace project (Reverse engineering Strike Commander) to my first modifications, and finally a brief update on where we are today.

The beginig

One day, I had the idea of reviving the SGI simulator (SGI Dogfight). While browsing the web, I found a Windows version along with its source code. However, the Windows version didn’t work correctly. Later, I discovered that our machines are simply too powerful, and the original code was designed to run at a frequency of 30 FPS. Beyond that, the calculations break down.

Since I had some free time, I decided to delve into the source code to understand the problem and try to fix it. The provided source code wasn’t from the Windows version, but from the original version for Silicon Graphics workstations, which used the predecessor of OpenGL. In short, a 1989-90 legacy C code in all its glory. But nothing impossible. I did some archeological work to find technical documentation and began porting it.

Once the porting was complete (Old flight source code), I realized I had a flight simulator codebase, and I thought, “It would be awesome to fly in other settings, like the maps from Strike Commander, F-19 Stealth Fighter, or other 90s flight simulators.” I started searching for information online and found some documentation about F-15 Strike Eagle III by MicroProse. I also came across Fabien Sanglard’s page detailing his reverse engineering work on Strike Commander. He had shared his work on GitHub.

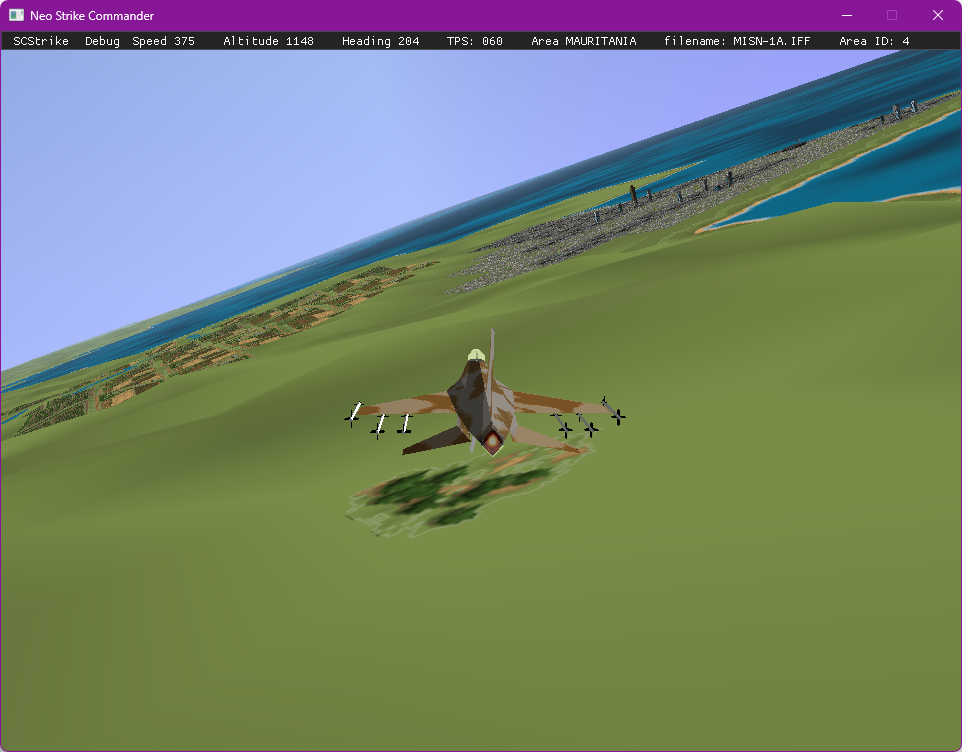

I downloaded the sources and compiled the project. Then, in a highly professional manner (read: completely improvised), I integrated the maps into my simulator. Now I could fly in the Strike Commander universe again! I even submitted a pull request (PR) to fix a bug related to object positioning on the map and informed Fabien Sanglard of my progress.

And like any good developer, I put the project on pause (thanks to Cyberpunk 2077).

After the break

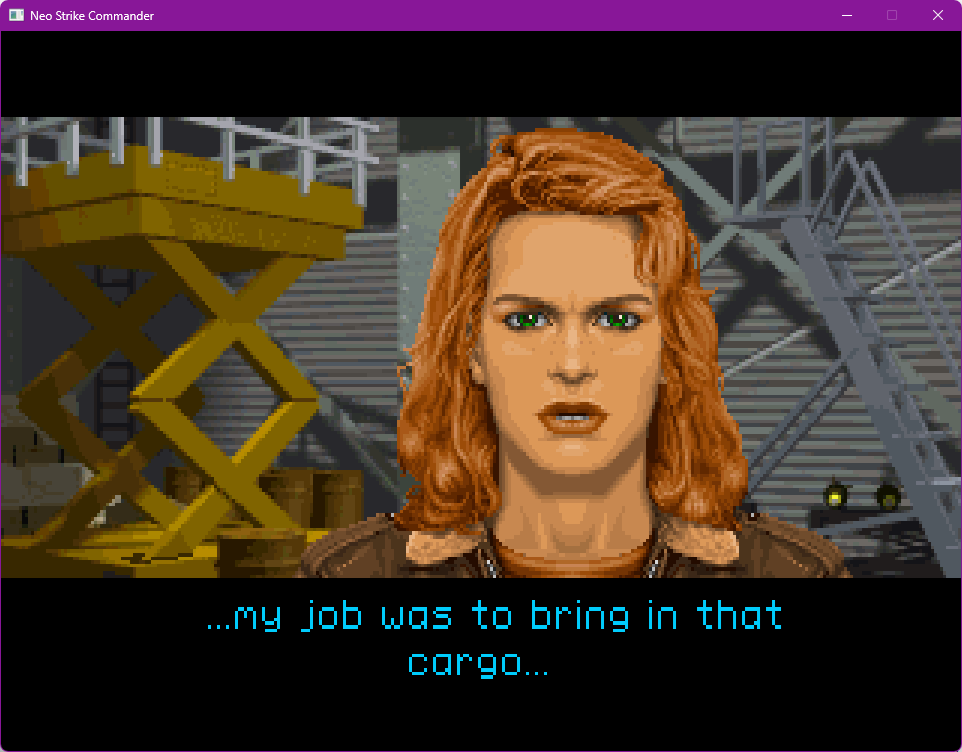

This summer, I decided it was time to revisit the project. Strike Commander is an arcade flight simulator with a strong emphasis on storytelling—the hallmark of Chris Roberts.

For the flight simulation part, I already had something in place. Now I needed to tackle the game’s presentation, its storytelling, conversations, and screens—all the surrounding elements. Unsure of where to begin, I started exploring the assets. There’s a community around Chris Roberts’ games (mainly Wing Commander) that has developed tools to mod them. So, I began extracting all the data. That’s when I realized the extraordinary effort they had put in back then. Once the assets were extracted, I ended up with around 300 megabytes of data—not bad for a game distributed on 8 floppy disks of 1.44 MB each.

After extracting the assets, I found myself facing an almost impossible task: how to connect all these animations, figure out which dialogue to display, which character to show on screen, and how to link the missions. I started making a kind of storyboard, but it quickly became too vast and overwhelming. It wasn’t a good start.

A bit discouraged by the enormity of the task, I began opening binary files and exploring their content to see if I could find anything useful.

The game uses the IFF format to store data for model definitions, missions, and management data in general. IFF is often associated with images and the Amiga. However, it’s a format developed by Electronics Arts (Interchange File Format), which is generic; the image version is just one possible use. It’s also used to store MIDI music in XMI files, among other things.

Still, knowing it was IFF was helpful, but I had hexadecimal data to work with, and hexadecimal wasn’t exactly my second language in school. I wrote some Python scripts to translate the files and make them more understandable for a human.

That’s when I had a revelation. There were two files that seemed cryptic at first but appeared to interact with each other. One mentioned SCEN (scenes), SPRT (sprites?), and the other referred to MISS (missions). By analyzing these hints, I realized I could retrieve character images. I had finally found the heart of the game. These two files, OPTIONS.IFF and GAMEFLOW.IFF, are used to manage everything outside the missions, the storytelling, dialogues, and possible choices are all in these files. A mini scripting system is used to manage choices and trigger actions.

To summarize, as bizarre as it might seem, the technical challenge of this port isn’t the 3D or flight simulation. While those are complicated, there are plenty of resources available to understand how to handle them, and even an average programmer like me can achieve something. Nothing extraordinary, and thanks to today’s powerful computers, there’s no need for optimization to get a decent frame rate (right now, I’m rendering the entire map with all objects at max resolution, 0 optimization, and it runs smoothly).

The real challenge lies in understanding and exploring the data to avoid re-coding things that are already present in the game’s original assets.

Essentially, I’m creating more of an emulator for Strike Commander than remaking the game. It’s a bit like ScummVM, really. And I can’t help but think that maybe this code will be able to run other Chris Roberts games built on the same engine (Real Space).

And Now

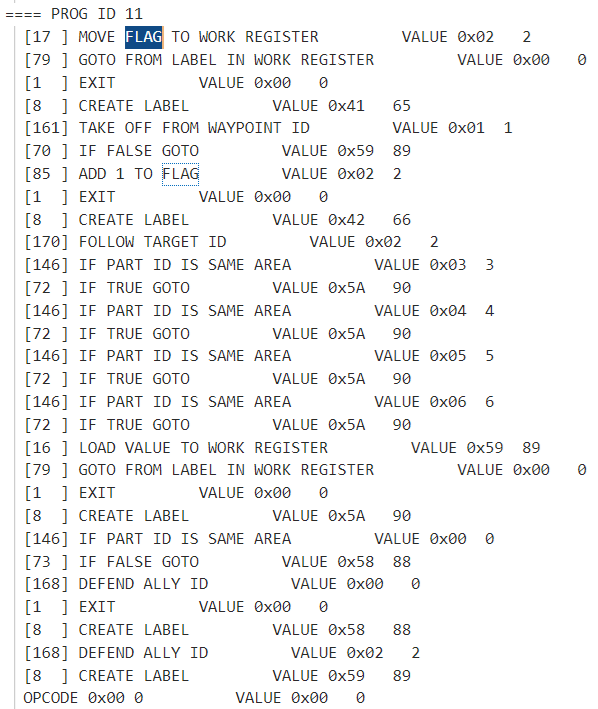

Recently, I’ve been working on another aspect of the game: managing mission scripts. Missions in Strike Commander are highly scripted, with events popping up and unexpected twists. However, the files were extremely cryptic. Aside from a few messages, there were no clear indications of what needed to be done. My only clue was an IFF chunk labeled “PROG.” Well, “PROG” as in “program”… that seemed promising, but beyond that, I was left with just a sequence of bytes—no documentation, no explanations.

Hope was sparked when I focused on the first part of the sequence. By examining several missions, I noticed many repeated bytes. Another sequence caught my attention: hexadecimal sequences like AA 01, AA 02, AA 03. Assuming AA was an instruction and 01, 02, 03 were values, what could these values represent? Well, they matched perfectly with the messages to be displayed on the map: “go to point 1,” “destroy the convoy.” And thus began the work of implementing mission scripts. There was no technical difficulty in coding, but deciphering what the developers had in mind was the real challenge.

To make progress, I used the original game as my reference, modifying mission files based on my findings to validate my hypotheses. Then, as I continued my research online, I stumbled upon documentation for a scripting system used in Wing Commander IV, released after Strike Commander, which described the scripting system. Having a list of the different instructions allowed me to confirm my discoveries and correct any incorrect assumptions I had made.

Once I completed the implementation, it was incredibly satisfying to see the game acknowledge that I had completed a mission. Yes, it happened in the game, but it also felt like a victory in real life… well, you know.

To Conclude

Where is the project today? I can say that it’s starting to become a game rather than just a technical demo of what’s possible. You can grab the source code (the project is open-source and available on GitHub: https://github.com/remileonard/libRealSpace), compile it on Linux or Windows (though the release is a bit dated…), retrieve the data from the original diskette version of the game, and play it. Not quite like back in the day, as there’s still work to be done on the AI, the game’s monetary system (where you earn money during missions to buy weapons and progress further), and—most importantly—displaying the cutscenes (ah, that glorious game intro!).

But the game is beginning to rise from the ashes, becoming playable again without the need for emulation on modern machines. So, I figured rather than keeping it to myself, maybe other players might be interested in rediscovering the sensations of the era and benefiting from modern hardware to enjoy the game under better conditions. My goal is to only enhance the game’s 3D aspects (back then, it felt like being in a world of perpetual fog). As for everything else, I want to preserve the original pixel art assets.